This is the 17:th post in a series about Microsoft SQL Server R Services, and the 16:th post that drills down into the internal of how it works. To see other posts (including this) in the series, go to SQL Server R Services.

In the last few posts in this Internals series we have looked at how data is being transported from SQL Server to the SqlSatellite. In this post we’ll look at how data is going the other way, from the SqlSatellite to SQL Server.

Before drilling down into the topic of today, let’s do a recap of some of the posts that have led up to where we are right now.

Recap

In Internals - X we saw how both the external script as well as data from @input_data_1 was sent over a TCP/IP connection to the SqlSatellite from SQL Server, and Internals - XI looked at some of the authentication packets sent from SQL Server to the SqlSatellite.

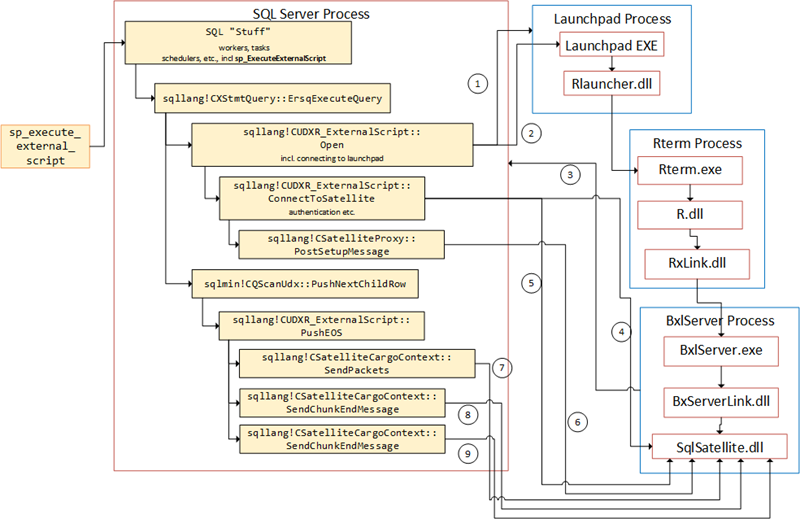

Internals - XII looked at from where the script and data packets are sent (what routines), and we determined that the script packet was sent while the sqllang!CSatelliteProxy::PostSetupMessage routine was called, and the data packet(s) was sent during the sqllang!CSatelliteCargoContext::SendPackets routine. In XII we also explained the two packets with a length of 28 we see in Figure 1 (being sent after the two data packets), as end packets. These packets tell SqlSatellite that no more data is coming. We illustrated the internal SQL Server flow like this:

Figure 1: Flow in SQL Server

I was unclear of when the statement in @input_data_1 was being executed, and [Internals - XIII] had a look at that and the conclusion we came to was:

- Before the SqlSatellite is initialized the statement is compiled.

- After the satellite has been initialized the statement is executed.

- If an error happens after the satellite has been initialized, SQL Server sends an abort message to the satellite in the

sqllang!CSQLSatelliteCommunication::SendAbortroutine.

Then, after “many a false starts”, I started talking about the Binary eXchange Language (BXL) protocol in Internals - XIV. BXL is a protocol optimized for fast data transfers between SQL Server and external script engines and it moves data in column oriented fashion, and utilizes schema information to optimize how to send the data.

When looking at the data sent, the size of the packages and “drilling” into the TCP packets we could deduct that: :

- Each column has an over-head of 32 bytes (at least for non nullable data)

- The size of the column in one row is the size of the data type for numeric types.

- For

decimalandnumerican extra byte is added to each column, where this byte indicates the precision. - Columns of alpha numeric type all had 2 bytes pre-pended to the bytes, except

maxtypes. - For

charandncharthe storage size was 2 bytes plus the size the column was defined as. - For

varcharandnvarcharthe storage size was 2 bytes plus the size of the data stored. - For the

varmaxdata types the number of bytes that were pre-pended varied dependent on the data size.

What happens with nullable columns is a mystery, as we saw column overheads ranging from 7312 bytes (tinyint) to 32 bytes (decimal), and I can’t help but think that there is a “bug” in there somewhere that causes this.

NOTE: This nullable “issue” will raise it’s head in this post as well.

So, in Internals - XIV we saw the packet sizes (over-heads etc.) for various data types, and in Internals - XV we looked at the packet sizes going over the wire. We compared it with TDS and saw how TDS sends multiple smaller packages where max size is by default the network package size (4536 bytes). BXL, on the other hand, tries to send as big packages as possible, where big in this instance is up to 65536 bytes. BXL creates a new package when the size of rows and columns has reached 65536.

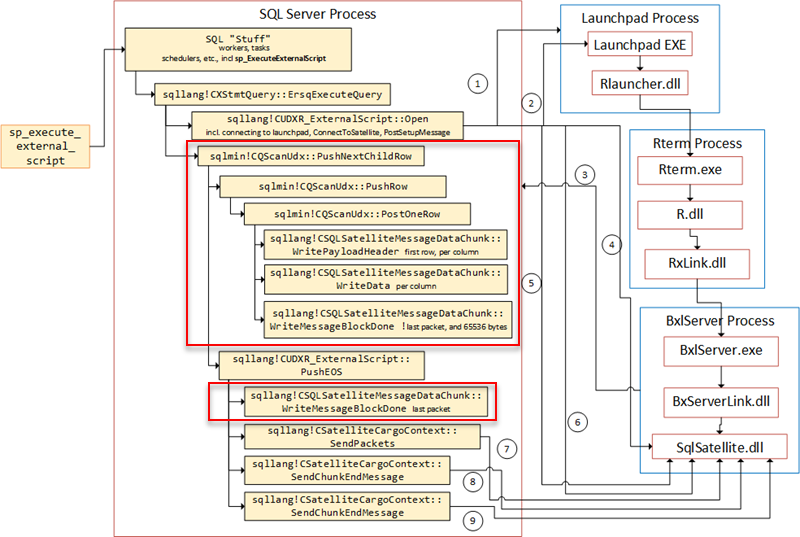

We also looked at the code in SQL Server that is being executed when sending the data, and we realized that the sqlmin!CQScanUdx::PushNextChildRow routine was where everything happened (or in sub routines). We were aware of that routine from Internals - XII, where we looked at what sent the TCP packets to the SqlSatallite. We saw how PushNextChildRow calls PushRow, which in turns call PostOneRow. Dependent on if it is the first row, PostOneRow calls WritePayloadHeaderfollowed by WriteData. If it is not the first row PostOneRow calls WriteData only. If the packet has reached the size of 65536 and there are more packets, WriteMessageBlockDone is called. If it is the last packet, PushEOS is called and PushEOS calls WriteMessageBlockDone. The figure below illustrates the flow:

Figure 2: BXL Code Flow

What we have recapped above should help us in this post.

Housekeeping

Housekeeping in this context is talking about the tools we’ll use, as well as the code. This section is here here for those of who want to follow along in what we’re doing in the posts.

Helper Tools

To help us figure out the things we want, we will use Process Monitor, and WireShark:

- Process Monitor, will be used it to filter TCP traffic. If you want to refresh your memory about how to do it, we covered that in Internals - X as well as in Internals - XIV.

- I’ll use WireShark for network packet sniffing. In previous posts I have used Microsoft Message Analyzer for this, but I am now back to WireShark as I find it gives me more readable output. If you want a refresher about WireShark, we covered the setup etc., in Internals - X.

Code

The code below sets up the database and creates some tables with some data. it is more or less the same as we used in Internals - XIV:

USE master;

GO

SET NOCOUNT ON;

GO

DROP DATABASE IF EXISTS ResultData;

GO

CREATE DATABASE ResultData;

GO

USE ResultData;

GO

DROP TABLE IF EXISTS dbo.rand_1M

CREATE TABLE dbo.rand_1M(RowID bigint identity primary key,

y int NOT NULL, rand1 int NOT NULL,

rand2 int NOT NULL, rand3 int NOT NULL,

rand4 int NOT NULL, rand5 int NOT NULL);

GO

DROP TABLE IF EXISTS dbo.test1;

CREATE TABLE dbo.test1

(

RowID int identity primary key, colint1 int NOT NULL, colint2 int NULL,

colint3 int NULL, colvchar1 varchar(50) NOT NULL,

colvchar2 varchar(50) NULL

);

GO

INSERT INTO dbo.test1

VALUES (1, 2, 5, 'A', 'B'),

(3, 4, 6, 'C', 'D');

INSERT INTO dbo.rand_1M(y, rand1, rand2, rand3, rand4, rand5)

SELECT TOP(1000000) CAST(ABS(CHECKSUM(NEWID())) % 14 AS INT)

, CAST(ABS(CHECKSUM(NEWID())) % 20 AS INT)

, CAST(ABS(CHECKSUM(NEWID())) % 25 AS INT)

, CAST(ABS(CHECKSUM(NEWID())) % 14 AS INT)

, CAST(ABS(CHECKSUM(NEWID())) % 50 AS INT)

, CAST(ABS(CHECKSUM(NEWID())) % 100 AS INT)

FROM sys.objects o1

CROSS JOIN sys.objects o2

CROSS JOIN sys.objects o3

CROSS JOIN sys.objects o4;

GO

Code Snippet 1: Database, and Database Object Creation

When you look at the database and the objects in Code Snippet 1, you’ll see it is more or less the same as we used in Internals - XV. The code you will execute is also very similar to what we did in Internals - XV, and the “base” code looks like so:

EXEC sp_execute_external_script

@language = N'R' ,

@script = N'OutputDataSet<-InputDataSet'

, @input_data_1 = N'SELECT TOP(1) rand1 FROM dbo.rand_1M'

Code Snippet 2: Base Code to Execute

The major difference between the Code in Code Snippet 2 and the code in Internals - XV, is that in the R script, we are “echoing” the incoming data from @input_date_1, to be the output as well: OutputDataSet<-InputDataSet. Let’s see this in action.

Output Data from R

We’ll start with testing that everything works, as well as seeing the port SQL Server listens on for communication with the SqlSatellite. To get the port we’ll use Process Monitor, and look at the Path column for the port.

NOTE: We need the path later on to set display filters in WireShark.

So this is what we’ll do:

- Run Process Monitor as admin.

- Set a filer to capture

TCP Receivein the processBxlServer.exe. - Execute the code in Code Snippet 2.

After you executed the statement you should see in Process Monitor the - by now - familiar data packets being sent. Amongst them there is a packet with a length of 36 bytes, and - as we know - this is the packet with the actual data.

NOTE: When you see the output from Process Monitor, don’t forget to see (and remember) what the port number on the SQL Server side is, you get it from the

Pathcolumn.

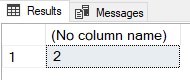

As the script now says OutputDataSet<-InputDataSet, whatever we send to the SqlSatllite is “echoed” back and sure enough, in SSMS we should see something like so:

Figure 3: Output Dataset

The reason why we in Figure 3, don’t see a column name is because we have not told SQL Server what it is supposed to be (we’ll cover that in a future post).

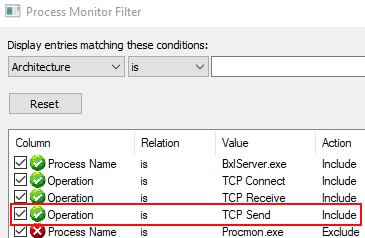

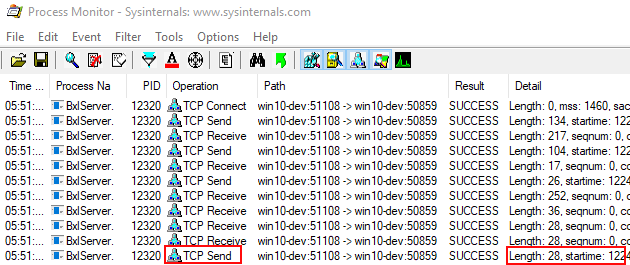

As everything seems to be in order, let’s look at what is being sent back to SQL Server. To do this we first of all need a new filter in Process Monitor, where we can see packets sent from BxlServer.exe in addition to the packets that are sent to it. The easiest way to accomplish this is just to add a new operation: TCP Send to the existing filter:

Figure 4: Send and Receive Filter

In Figure 4 you see what the filer should look like, and it may be a good idea to save this filter for future use. As we are interested in what is being sent back to SQL Server after SQL has sent the data, let’s change the code in Code Snippet 2 slightly, and introduce a Sys.sleep. That will allow us to more easily see when (and what) data comes back:

EXEC sp_execute_external_script

@language = N'R' ,

@script = N'Sys.sleep(20)

OutputDataSet<-InputDataSet'

, @input_data_1 = N'SELECT TOP(1) rand1 FROM dbo.rand_1M'

Code Snippet 3: Code with Sleep

When you execute the code in Code Snippet 3, Process Monitor will output something like so (followed by a pause):

Figure 5: Sending and Receiving - I

Figure 5 shows the data being sent from SQL Server and received by SQL Server, and we see how:

- SqlSatellite receives the script is (length 252), followed by

- the actual data (length 36 - as was discussed in Internals - XIV), followed by

- the two “end” packages (length 28).

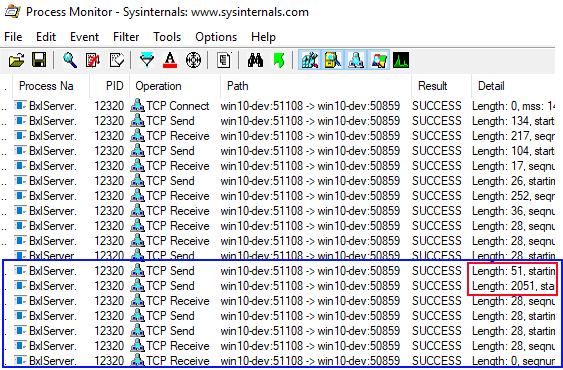

Then, the highlighted data in Figure 5, SqlSatellite sends a packet with a length of 28. This packet is an ack packet, and is for this discussion not interesting. At this stage, the code is now pausing. After ~20 seconds Process Monitor outputs the “rest” (outlined in blue):

Figure 6: Sending and Receiving - II

The really interesting part of Figure 6 is what is outlined in red; two packets with a length of 51, and 2051 respectively. Why do I say they are interesting? Well, change the @input_data_1 parameter to be SELECT TOP(1) rand1, rand2 FROM dbo.rand_1M and execute. This results in two packets with lengths of 69 and 4074, which indicates that these packets have something to do with the data being returned from the SqlSatellite.

So, let’s see if we can prove that these two are related to the data being sent back from the SqlSatellite. Oh, and there are also some questions related to these packets:

- Why two packets, when we are sending only one data packet?

- Which packet contains the data?

- Why is one of the packets so big?

What we will do in order to try to figure out this is to execute the code in Code Snippet 3 with different @input_data_1 statements. The statements will return different number of columns and rows, and from seeing the sizes coming out of that we may be able to deduct how things work. The statements we’ll execute are these:

-- one row, one column

SELECT TOP(1) rand1 FROM dbo.rand_1M

-- two rows, one column

SELECT TOP(2) rand1 FROM dbo.rand_1M

-- one row, two columns

SELECT TOP(1) rand1, rand2 FROM dbo.rand_1M

-- two rows, two columns

SELECT TOP(2) rand1, rand2 FROM dbo.rand_1M

-- one row, three columns

SELECT TOP(1) rand1, rand2 FROM dbo.rand_1M

Code Snippet 4: Different @input_data_1 Statements

After executing the code with the statements in Code Snippet 4 we see following sizes (R stands for row, C for column):

| Packet | 1R, 1C | 2R, 1C | 1R, 2C | 2R, 2C | 1R, 3C |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| small pkt. | 51 | 51 | 69 | 69 | 87 |

| large pkt. | 2051 | 2055 | 4074 | 4082 | 6097 |

Table 1: Packet Sizes

From what we see in Table 1 we can say that the “small” packet probably does not contain any data, seeing that when comparing the size for one column, one row with two rows one column, it has the same size (51 bytes). However, it definitely looks like the number of columns has an impact: 1 column 51 bytes, 2 columns 69 bytes, and finally three columns 87 bytes, which also tells us that each column adds 18 bytes to the size. So, it look like the “small” packet has something to do with the columns coming back. We’ll leave this packet for now and come back to it in next post.

The “big packet” definitely looks like it has something to do with the data coming back: one row, one column has a size of 2051, and two rows one column 2055. That’s 4 bytes more, the same size as an int. But, once again why such a big packet, this is like what we saw in Internals XIV when data is sent to the SqlSatellite originating from nullable columns?

That is the answer, when returning numeric data from the SqlSatellite, the data is treated as it would originate from nullable columns. Character based data has the same behavior as when sending data to the SqlSatelllite - so not the big overhead when coming from nullable columns. There are though some differences between character data sent to SqlSatellite and character data coming back, and I’ll point out some of it below.

So, numeric data sent back from the SqlSatellite looks almost like nullable numeric data sent to the SqlSatellite. One difference though is the size for the first column; if you look in Table 1 you see the size for one row, one column be 2051. When we look in Table 2 in [Internals - XIV], the size for an int is 2023, so it seems there is a 28 bytes extra somewhere. Incidentally, 2023 is the difference between returning one row, one column and one row two columns. So it looks like that the 28 bytes overhead only occurs once.

Perhaps we can figure out what happens by doing some WireShark “sniffing”. If you look at the table dbo.test1 you see it has two nullable int columns: colint2 and colint3, and it is these two columns we’ll use when trying to figure out what happens. Before we involve WireShark, we’ll:

- Change the

@input_data_1parameter to be:SELECT TOP(1) colint2 FROM dbo.test1. - Execute and check the packet sizes in Process Monitor.

- Check the port number in the

Pathcolumn in Process Monitor.

In the output from Process Monitor we should now see one packet being sent to the SqlSatellite with a length of 2023, and a packet being sent to the SQL Server with a length of 2051. The assumption we’re making is that those packets are identical, except for the 28 bytes overhead. Now it’s time for WireShark:

- Run WireShark as admin.

- Choose the network adapter to “sniff” on. See Internals - X for discussion around loop-back adapters etc.

- Set a display filter on the port SQL Server listens on. In this case we want to sniff outgoing as well as incoming packets, so the filter should be:

tcp.port==xyz. - Apply the filter.

After you execute the code what you’ll see in WireShark is quite a few packets being sent from and to the SQL Server port:

Figure 7: WireShark Packets

NOTE: When packets are sent over the network they are sent in chunks. WireShark captures each chunk individually, whereas Process Monitor shows the full package. That’s why you see multiple packages in WireShark, but only one in Process Monitor.

In Figure 7 we see - outlined in blue - two packets with a size of 1460 and 563. That’s the data packet sent to SQL Server, reported in Process Monitor as one packet with a length of 2023. Outlined in red we see the two packets containing the actual data going back to SQL Server from the SqlSatellite, with lengths of 1460 and 591 (2051 total). Let’s now compare the packet sent to the SqlSatallite with what is coming back, and we’ll start with the first 64 bytes of the two packets:

//packet sent to SqlSatellite

01 00 07 80 e7 07 00 00 04 c1 82 01 79 63 a7 48 ........ ....yc.H

a0 c8 c0 ab d8 cb 27 61 00 00 07 3e 00 00 00 00 ......'a ...>....

01 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ........ ........

00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ........ ........

//packet received from SqlSatellite

01 00 07 80 e7 07 00 00 04 c1 82 01 79 63 a7 48 ........ ....yc.H

a0 c8 c0 ab d8 cb 27 61 00 00 07 3e 00 00 00 00 ......'a ...>....

01 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ........ ........

00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ........ ........

Code Snippet 5: Packets Sent to and Received from SqlSatellite

Remember how we in Internals - XIV said that the BXL protocol has a column overhead of 32 bytes, but that we don’t really know what it contains. In Code Snippet 5, we see the first 32 bytes of the two packets are exactly the same, e.g. a column header - so it is probably safe to say that the BXL protocol is used also when returning data from the SqlSatellite. The remainder of the two packets looks also identical - up until the end:

//packet sent to SqlSatellite

00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ........ ........

00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 02 ........ ........

00 00 00

//packet received from SqlSatellite

00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ........ ........

00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 02 ........ ........

00 00 00 01 00 06 80 1c 00 00 00 04 c1 82 01 79 ........ .......y

63 a7 48 a0 c8 c0 ab d8 cb 27 61 01 00 00 00 c.H..... .'a....

Code Snippet 6: End Part of Packets

When looking at Code Snippet 6 we see that the last 4 bytes of the first packet represents the value of the column: 2 which in hex is 02 00 00 00. But looking at the packet coming back from the SqlSatellite we see that there are more data after the value. In fact - when we look at it, it turns out to be 28 bytes. Those 28 bytes look very much the same as the starting bytes, but not totally identical. If we change the statement for @input_data_1 to be: SELECT TOP(1) colint2, colint3 FROM dbo.test1 and execute, we’ll see how the 28 bytes extra appears at the end of the packet, almost like a separate row. Thinking back to the TDS discussion in Internals - XIV, this feels like an end sequence, and we’ll revisit this in next post.

So out of the three question was asked above (why two packets, etc.) we have answered two - or rather we assume that the first packet is there for something column related, and we have seen how the second packet contains the actual data. The third question then, why is the packet containing the data so big? The answer to that (as far as I can tell) is that the data originating in the R engine, is always considered being nullable. Then the “bug”/feature that we spoke about in Internals - XIV raises its head, whereby “nullable” data gets a quite big overhead.

Numeric Types

Let’s look at numeric types and see what it gives us in terms of overhead. In the case of an int, coming back from SqlSatelite - the actual overhead is 1987 bytes excluding any data, end sequence, column overhead, etc. (1987, plus 4 bytes for the value, plus 32 bytes for the column, plus 28 bytes for the “end-sequence” gives us 2051). So do we then have the same behavior for all nullable numeric data types that we saw in Internals - XIV:

| Data Type | 1 Row | 2 Rows | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|

| tinyint | 7313 | 7314 | - |

| smallint | 3889 | 3891 | - |

| int | 2023 | 2027 | - |

| real | 2023 | 2027 | - |

| float | 2023 | 1050 | 2027 | 1058 | Based on storage size 4 or 8 bytes |

| bigint | 1050 | 1058 | |

| money | 1050 | 1058 |

Table 2: Nullable Packet Sizes to SqlSatellite

In Internals - XIV we saw the table above, and it listed the data sizes of packets sent to the SqlSatellite from SQL Server, where the data originates from nullable columns (the sizes above include the data size, and the 32 bytes column header). When looking at data coming back from the SqlSatellite you’d think that you’d see the sames sizes (plus the 28 bytes end-sequence), but that is not the case:

| Data Type | 1 Row | 2 Rows | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|

| tinyint | 2051 | 2055 | - |

| smallint | 2051 | 2055 | - |

| int | 2051 | 2055 | - |

| real | 1078 | 1086 | - |

| float | 1078 | 1086 | No difference related to storage size |

| bigint | 1078 | 1086 | |

| money | 1078 | 1086 | |

| decimal | 1078 | 1086 | No difference related to storage size |

Table 3: Packet Sizes from SqlSatellite

Notice in Table 3, how - when data comes back from SqlSatellite - there are only two packet sizes (2051, 1078) regardless of data type. In addition we see decimal in the table, whereas when sending to SqlSatellite, there were no overhead for nullable decimal. The reason for only two sizes coming back is that whereas

SQL Server supports quite a few data types, R has a limited number of scalar data types. So, whenever you use data from SQL Server in R scripts, the data might be implicitly converted to a compatible data type.

What is interesting in the paragraph above, or rather what the paragraph above implies; is that when data goes to the SqlSatellite - somewhere in the packet it contains type information, and that is most likely in the 32 bytes column “header”. Also interesting is that if you send the value 1 as an int, and the value 1 as a bigint you get different packet sizes returning - event though they are treated as nullable.

Alpha Numeric

What about alpha-numeric data types? Alpha numeric data has actually the same behavior when coming back from SqlSatellite as it does when sending data to SqlSatellite. With that I mean that nullable column data has no impact - no extra overhead is added to the data coming back. There are however some differences; remember what we said in Internals - XIV, and also in the Recap above, about sending alpha numeric to SqlSatellite:

- There is the “usual” 32 bytes column overhead.

- Columns of alpha numeric type all have 2 bytes pre-pended to the bytes, except

maxtypes. - For

varcharandnvarcharthe storage size was 2 bytes (the 2 bytes mentioned above) plus the size of the data stored (single bytevarchar, double bytenvarchar).

NOTE: I am not covering

maxtypes here, as I do not think there will be that many instances ofmaxtypes being returned to SQL Server from SqlSatellite.

When alpha numeric data comes back from the SqlSatellite however

- There is the “usual” 32 bytes column overhead as before, plus the 28 bytes end-sequence.

- Instead of 2 bytes pre-pended, each column has 4 bytes pre-pended.

- The data coming back is always in double-byte format, so one character comes back as 2 bytes.

An example of this is, in the table dbo.Test1 there is a column colvchar1, and the first row has the value of A, the second a value of B. When executing the code in Code Snippet 2 with the @input_data_1 statement being: SELECT TOP(1) colvchar1 FROM dbo.Test1, the sizes are:

- Going to SqlSatellite: 35 bytes (32 bytes column header + 2 bytes per column + 1 byte for the value).

- Back from SqlSatellite: 66 bytes (32 bytes column header + 28 bytes end sequence + 4 bytes per column + 2 bytes for the value).

When selecting TOP(2) the sizes are:

- Going to SqlSatellite: 38 bytes (35 from 1 row + 2 bytes per column + 1 byte for the value).

- Back from SqlSatellite: 72 bytes (66 bytes from one row + 4 bytes per column + 2 bytes for the value).

Summary

In this post we looked at data being returned from the SqlSatellite to SQL Server. We saw how there were actually two packets coming back, one small and one bigger, we deduced that those packets were:

- The smaller packet had something to do with column meta-data.

- The bigger packet held the actual data.

For numeric data types coming back:

- The data was treated as originating from nullable columns (with a large overhead).

- The data packet contained a 28 bytes end sequence.

Due to R not supporting all data types that SQL Server supports, the data was casted to compatible R types.

In next post we’ll look at the code involved in SQL Server as well as the launchpad service, when data comes back. Doing that we’ll also hope to be able to understand more about the smaller packet coming back, as well as the end sequence.

~ Finally

If you have comments, questions etc., please comment on this post or ping me.